A most unusual train connected Dun Laoghaire and Dalkey for 10 years, until the last journey took place on this day 1854, and the railway closed. It was the end of an era, and an unusual experiment in railway design. But you can still follow the route of the train, and still see the Atmospheric Road street sign at Dalkey.

Where most trains had an engine to pull the train, Dalkey’s ‘atmospheric’ train had no engine, and instead, the train was essentially “sucked” up the hill by a steam engine located beside the track. This alternative arrangement called for a complicated track design, and there were frequent technical problems, so it was no surprise when the railway closed after 10 years.

Rival designs

For their first 25 years, railways were marred by the ‘war of the propulsion systems’. On one side were George and Robert Stephenson, who pioneered the railway locomotive. Opposing them was Isambard Kingdom Brunel who favoured engine-less trains.

Brunel thought that attaching a heavy locomotive to a train was crazy: the engine had to haul its own weight, a substantial railway was needed to bear the combined weight of train and engine, and the steam engine made for a noisy, smoky and rough ride. It would be faster, cheaper, safer and more comfortable to generate the power elsewhere with a fixed engine, transmit the power to the railway, and run a lightweight train of carriages on a correspondingly lightweight track. You can see a certain logic to his argument.

Various engine-less systems were devised – some, such as ‘rack and pinion’ trains and cable cars, are still used – but the main contender was Brunel’s ‘atmospheric’ or pneumatic railway, so-called because the fixed steam engine generated suction power to move the train.

Following successful experiments with small-scale models, the developers of the new Kingstown [as Dún Laoghaire was then called]–Dalkey railway opted for Brunel’s idea and, in July 1844, opened the world’s first commercial atmospheric railway to considerable international attention. (Brunel’s South Devon atmospheric railway opened some months later on an experimental basis, was not fully operational until 1847 and closed a year later.)

A steam engine in Dalkey generated the power to pull the trains uphill from Kingstown; for the return journey they simply fell slowly downhill under gravity – and if the momentum was not enough to carry the train into Kingstown station, third-class passengers were expected to get out and push!

Intricate design

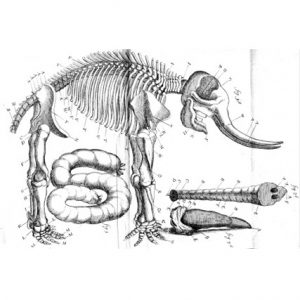

The pneumatic system was intricate: a cast-iron pipe was laid between the railway tracks, and an airtight piston in the pipe was connected to the train. The steam engine at Dalkey pumped air out of the pipe ahead of the train, creating a vacuum; and the atmospheric pressure of the air behind the piston pushed the train along. You can see the central pipe beneath the train, in the illustration above, from the 1844 opening.

The pipe had a narrow slot along its top through which the piston arm moved. A complex flap and valve system let the piston arm pass, but otherwise kept the slot closed. Wheels and rollers on the underside of the train manoeuvred the flap open, and pressed it back in place afterwards. To ensure a tight seal the flap was also greased. But maintaining an airtight seal was difficult: the grease attracted rats that ate the leather; in summer, the grease melted away; and in winter the leather froze. Running the pumping station intermittently was also costly.

World’s 1st commercial atmospheric railway

Nevertheless, the Kingstown–Dalkey railway operated for 10 years, following the old tramway cutting between Dalkey quarry and Kingstown. It was quite a service to0: trains ran every half-hour between 8am and 6pm, averaging 48 kmph uphill to Dalkey, and 32 kmph when falling to Kingstown.

However, in 1848, the South Devon Railway Company, believing they were losing money (they were actually making a handsome profit), pulled the plug on their atmospheric railway, handing victory to Stephenson and his locomotives. Dalkey’s atmospheric railway survived until 1854, when it was converted to a conventional track and gauge, that is now part of the local DART line, and a Parisian line continued until 1869.

Modern air-driven trains

Atmospheric railways are again on the move: a Brazillian inventor Oskar Coester designed a new “aeromovel” system in the 1970s. The Aeromovel Corporation has now built several air-driven ‘people movers’ in Brazil and Indonesia.

Meanwhile, Dalkey’s original atmospheric line survives as a popular walking route, however, known locally as ‘the metals’.

This is an extract from our book, Ingenious Dublin, Mary Mulvihill’s guide to the city’s marvels, discoveries and inventions. The book is packed with hundreds of fascinating stories, and illustrations, and is available on Amazon for Kindle.

Thanks to Tim Joy for info on the Paris line, and the new Brazil railways.

Comments are closed.