Maynooth Science Museum, highlight of Dublin City of Science 2012

Do you like a good story? Interested in geeky history and science? Then you’ll love the wonderful museum in St Patrick’s College, Maynooth. Well worth a visit, it is in our online Atlas of Ingenious Ireland. And for more great stories like this, check out our new ebook about Dublin’s scientific heritage, Ingenious Dublin (the first chapter is free to download!).

Maynooth museum celebrates one of Ireland’s greatest inventors: a great pioneer of electricity, an Irish priest who, in the 1830s, built the most powerful magnet and battery in the world, invented the induction coil (which is still used in car spark plugs) and made it into the Encyclopaedia Britannica! This is his story…

A priest, a battery and a turkey

Rev Nicholas Callan (1799-1864) must have seemed like an Irish Frankenstein, experimenting with electricity in his laboratory at Maynooth College, dishing out almighty electric shocks to unsuspecting volunteers, even electrocuting turkeys.

Callan, from County Louth, was the first major Irish scientist from a Catholic background. He studied for the priesthood at the Irish College in Rome, where he learned about Alessandro Volta’s battery, a chemical device that could store electricity. Callan came home to teach science at St Patrick’s College seminary in Maynooth, and with funding from friends and family, he set about designing better batteries.

Callan’s battery was the Duracell of the day: the first truly cheap and effective battery.

Callan’s battery was the Duracell of the day: the first truly cheap and effective battery.

The world’s biggest battery

Electricity was still something of a toy then, but Callan realised that with powerful batteries it could be put to practical use. Where existing batteries used costly platinum, Callan found a way of using cheap cast-iron: his positive plate was a small cast-iron box filled with strong acid; in it sat a porous pot, also filled with acid, and containing a zinc sheet as the negative plate.

His most successful battery design sold commercially in London as ‘the Maynooth battery’. The ‘Duracell’ of its time, it was hard-wearing and cheap, long-lasting and powerful, and Callan hoped it would be used for lighthouse lamps and remote navigational buoys, but electric lighting was still in its infancy.

Callan used to connect large numbers of these battery cells, and once joined 577 (!) together, using 30 gallons of acid. It was the world’s largest battery. Since there were no instruments to measure current then, Callan assessed his batteries by the weight they could lift when connected to an electromagnet. His best effort lifted two tons and made it into the Encyclopaedia Britannica (8th edition) as the world’s most powerful magnet. When Callan reported his results in the Annals of Electricity, a London professor came to Maynooth to witness the spectacle and was said to be ‘incredulous’.

Inventing the induction coil

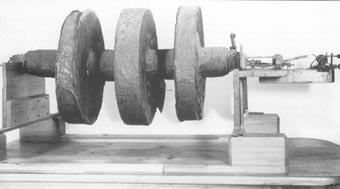

In 1836 Callan made his most important discovery – the induction coil. He wound two long wires around the end of his large electromagnet and connected the ends of one wire to a battery. But when he interrupted the current from the battery, he got a spectacular spark between the ends of the second, unconnected coil. It was the world’s first transformer.

He had induced a high-voltage in the second wire, starting with a low voltage in the first one. And the faster he interrupted the current, the bigger the spark. In 1837 he produced his giant induction machine: using a clock escapement to cut the current 20 times a second, he generated 15-inch sparks – an estimated 600,000 volts – and the largest artificial bolt of electricity then seen.

The coils were made from miles of hand-drawn metal wire which Callan laboriously insulated by hand using tape and wax. A model was sent to London for demonstrations and similar machines soon appeared in Europe and North America.

Roast turkey

The voltmeter had not been invented so to measure the voltage from his induction coils, Callan improvised. He would electrocute large birds, or shock chains of volunteers holding hands. One almighty shock rendered a future archbishop of Dublin unconscious, after which the college asked Callan to limit his experiments.

Callan’s induction coil is today used in car ignitions, for example, to generate powerful voltages from a low-voltage battery and produce sparks to cross the gap in the spark plug.

In 1838 this intrepid priest stumbled on the principle of the self-exciting dynamo. Simply by moving his electromagnet in the Earth’s magnetic field he found he could produce electricity without a battery. The effect was feeble, however, so Callan never pursued it, and the discovery is generally credited to Werner Siemens in 1866.

Electric pioneer

Callan probably also had one of the world’s first electric vehicles: in 1837 he was using a primitive electric motor to drive a small trolley around his lab. With great foresight he also predicted electric lighting, at a time when oil was still widely used and gas was the next new thing.

In 1853 he patented an early form of ‘galvanisation’, using a lead-tin mix to protect iron from rusting. He even proposed using batteries instead of steam engines on the new-fangled railways. Callan later realised his batteries were not powerful enough and it took a hundred years before battery-powered trains invented by another Irishman, James Drumm, were used on Dublin railways.

Visit Maynooth Museum

The wonderful museum has all of Nicolas Callan’s inventions and instruments, and even patent documents from his inventions. It also has a lovely and extensive collection of historic scientific instruments, including some of thoseused by Marconiwhen he was pioneering commercial radio in Ireland in the late 1800s. A separate section of the museum has religious artefacts, associated with the seminary.

Opening hours: the museum is open May-September Tuesdays and Thursdays (2-4pm) and Sundays (2-6pm), and October-April by appointment. For Science Week 2012, the museum is open Saturday afternoon, November 17 2-5pm. The museum is also one of the highlights of Dublin City of Science 2012 programme.

If you like this, you’ll also enjoy our guided tours of Ingenious Dublin, and our book about Ingenious Dublin — marvels, inventions and discoveries. The chapter about the Liffey, port and Dublin Bay is free to download from Amazon. More about the Ingenious Dublin book here.

I not to mention my buddies were found to be viewing the nice solutions on the website then immediately developed an awful feeling I never expressed respect to the site owner for those secrets. Most of the boys were definitely totally warmed to learn all of them and have in effect undoubtedly been enjoying those things. Many thanks for indeed being simply helpful and also for deciding upon this kind of awesome tips most people are really desperate to discover. My personal sincere apologies for not saying thanks to you earlier.

Hello. And Bye.